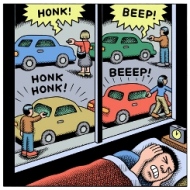

August 26, 2014 | This month I moved back to Brooklyn after two years of living in the Bronx. Time was limited, so the apartment hunt was kamikaze-style. I wound up renting a top floor studio apartment that not only faces the street, but overlooks a small private parking lot. After two years in a top-floor apartment overlooking lush greenery and a private park, buffered from all street noise by a broad cluster of buildings, it was a tough decision. Unfortunately, there just wasn't time for a reasonable search.

When I found the Bronx apartment in the summer of 2012, I was more than a year into researching and writing about horn-based vehicle alerts. The technology's constant intrusion into my street-facing brownstone apartment fueled my resolve to find an apartment that was physically at least a block's length from any parked car. My top requirement was that no matter how far I craned my neck out of any window, I would not be able to see a single parked car.

I knew they'd be there, somewhere around the corner, beyond where I could see. And there they were, Right on the other side of the building, right around the corner. But where I lived, facing away from them, my wide brick building created a sound barrier. They were there, and I could hear them - but they sounded far, far away. I could sleep at night with open windows, able to tune out the faint faraway horn sounds, or I could close the windows and not hear them at all - something that had been impossible two years ago in Brooklyn, where I'd lived ten feet from the street.

From a distance, each time I heard a car owner park and honk the horn, I experienced the perspective of the blissfully ignorant: like the product developers who brought us this technology: Just like them, I didn't care. From that distance, the noise had no effect on me. And I understood why they don't care, why this is not a problem for all of the people who have the power to change this but don't even know what "this" is.

In my Bronx community, there were other horn sounds as well. There were scores of livery cab drivers who traveled along our narrow, tree-lined streets honking at every pedestrian they saw, looking for fares. Some did not even look at pedestrians, but stared ahead as they drove past each block. There were also livery drivers - or friends, or family members - who arrived in front of buildings and blasted their horns to let residents know their ride was there. This occurred day and night, at three in the afternoon and three in the morning. Some livery drivers would drive into private parking lots at seven or eight in the morning without a ride having been ordered, and honk for a few minutes in case someone happened to need a ride.

When this happened, there I was on the other side of the building, buffered from the worst of the sound, hearing the horns only faintly, but knowing how it sounded to the people facing the street or the parking lot, thinking, never again will I be able to live facing a street - if I ever have to face a street again, I will die.

But I'm here, facing a street, overlooking a parking lot, and I'm still alive. I know that this is temporary. And I know that that other reality exists - I was there. After two years in Brooklyn with closed windows, ear plugs, and a white noise machine, and still being awakened when people parked their cars and honked their horns, I was able to fall asleep with the windows flung open so I could hear nearly horn-free night sounds, wind in the trees, and in the distance, cars on the Cross Bronx Expressway. Outside my window late at night, I measured sound levels - often as low as 38 decibels (same as the "lowest decibel reading taken in New York City").

In my new apartment, the windows remain closed, and I've created a wall of buffering sound made of wind, and sometimes, music. I've learned that having multiple sources of white noise placed in different places throughout the space will keep some of the horn noise out. An air conditioner. A large fan. The trusty SleepMate white noise machine. The layout in this apartment is different from that of my previous Brooklyn apartment, and it also helps to be seven stories up, rather than two, which had positioned me that much closer to lock alert horn honking. I also use a soundproofing curtain - it mostly reduces distant sound, but still, it helps. But as soon as I turn everything off before leaving for work in the morning, the honking is clearer, and closer - it never really went away.

I'm determined, as much as possible, not to let this setback discourage me. Just because I know that a quieter existence is 'right around the corner on the other side of any building,' I am not giving up the effort to eliminate this ultimate of Kafkaesque situations. It is absurd to consider the fact that people who face the street are exposed to dozens if not hundreds of horn honks as people park their cars - or as people lie in bed and honk the horn for one more dose of reassurance - at one, two, or three in the morning - while others are protected. And it is so disheartening to know that people in positions to change this at the drop of a dime are unable to imagine an experience that is different from theirs. But for a while, it was interesting - and so blissfully peaceful - to understand what their everyday experience is. That peace, that relative quiet, that assurance of a good night's sleep should not be luxuries - they should be available to everyone.

The ability of enclosed buildings to buffer backyards and courtyards from traffic noise is well documented. Residents who live on the "quiet side" of a building are afforded a level of peace and tranquility not experienced by those living on the street facing side. In residential bedroom communities and less dense suburbs, the elimination of horn-based lock alert sounds can restore a baseline level of peace and quiet. In denser, urban spaces, the elimination of lock alert horns can still improve ambient neighborhood noise.

As a wise Tesla owner wrote, "I am tired of people thinking that since it is currently noisy in an area they should add more noise. Did anyone ever stop and think that maybe it would not be so noisy in the area if people spent more time eliminating noise?"